Aspects of spatial planning

We work hard with our partners to incorporate the latest scientific research and planning priorities into our spatial plans, including Multiple-Use, Ecosystem Services and Climate-smart planning.

Multiple-use

As global demands for food, energy, and infrastructure continue to rise, competition for limited land and ocean space is intensifying. This creates growing tension between conservation objectives and economic development, particularly in coastal and marine regions where multiple industries—such as fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, and renewable energy—converge. Multiple-use spatial planning offers a promising pathway to balance these competing needs, but there remains a lack of practical guidance on how to implement it effectively. Key challenges include integrating diverse sectoral priorities, anticipating the economic impacts of spatial decisions, and ensuring planning tools are both scientifically robust and accessible to practitioners with varying levels of technical capacity.

To address this gap, we are developing a zoning approach within the shinyplanr application that explicitly supports multiple-use planning. By incorporating zones—such as those used in urban zoning schemes—into marine and terrestrial planning scenarios, users will be able to explore and visualize trade-offs and co-benefits across sectors in a transparent and data-driven way. This is especially critical in densely used inshore areas where spatial conflicts are most acute. Building on the prioritizr framework already used in Waitt Institute planning, we are working to expand functionality in shinyplanr and improve computational performance for more efficient scenario testing. These enhancements will make multiple-use spatial planning more accessible, scalable, and practical for real-world decision-making.

Ecosystem services

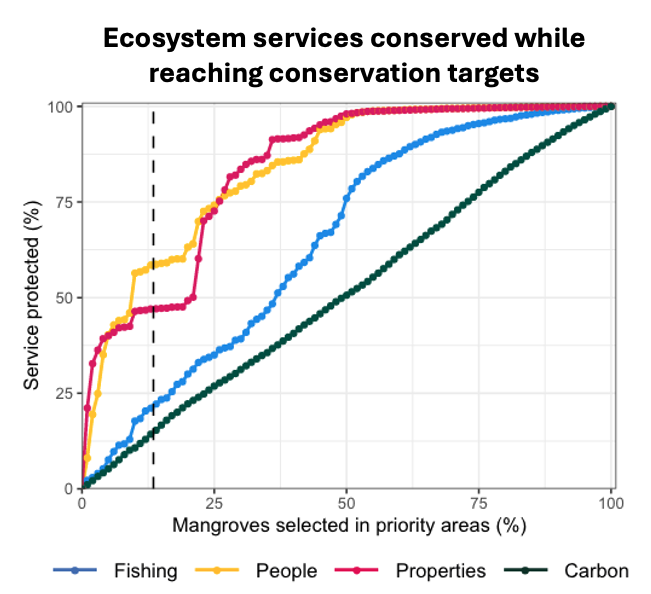

Conventional spatial planning approaches often prioritise minimising conflict with extractive industries, typically by excluding economically valuable areas such as heavily fished zones from conservation. While this reduces resistance from stakeholders, it limits the ecological effectiveness and long-term benefits of marine protected areas (MPAs). A growing body of research, including that of Dabala et al. (2023), highlights the missed opportunities in not accounting for the multiple ecosystem services provided by key coastal habitats. These services include carbon sequestration by seagrasses and mangroves, coastal protection offered by coral reefs, and critical nursery habitats for commercially important fish species. Despite their importance, these benefits are rarely quantified or directly integrated into spatial planning decisions, representing a major scientific and practical gap.

Conventional spatial planning approaches often prioritise minimising conflict with extractive industries, typically by excluding economically valuable areas such as heavily fished zones from conservation. While this reduces resistance from stakeholders, it limits the ecological effectiveness and long-term benefits of marine protected areas (MPAs). A growing body of research, including that of Dabala et al. (2023), highlights the missed opportunities in not accounting for the multiple ecosystem services provided by key coastal habitats. These services include carbon sequestration by seagrasses and mangroves, coastal protection offered by coral reefs, and critical nursery habitats for commercially important fish species. Despite their importance, these benefits are rarely quantified or directly integrated into spatial planning decisions, representing a major scientific and practical gap.

To address this, we are identifying key ecosystem services from the most common coastal habitats in planning regions—namely coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds. Our approach focuses on explicitly incorporating these ecosystem service data into conservation prioritisation, allowing for more holistic spatial planning outcomes for coastal communities. We aim to highlight the value proposition of conservation, beyond biodiversity gains and highlighting the critical and tangible socio-economic benefits. This work will not only support more resilient protected areas but also enhance stakeholder buy-in and implementation success by linking conservation with ecosystem service provision that directly benefits coastal communities.

Climate-smart

Climate change is compromising the effectiveness of established protected areas by transforming communities, driving local extinctions, and causing species to shift beyond the boundaries of protected areas.

Climate change is compromising the effectiveness of established protected areas by transforming communities, driving local extinctions, and causing species to shift beyond the boundaries of protected areas.

The Challenge: Protected today, unprotected tomorrow

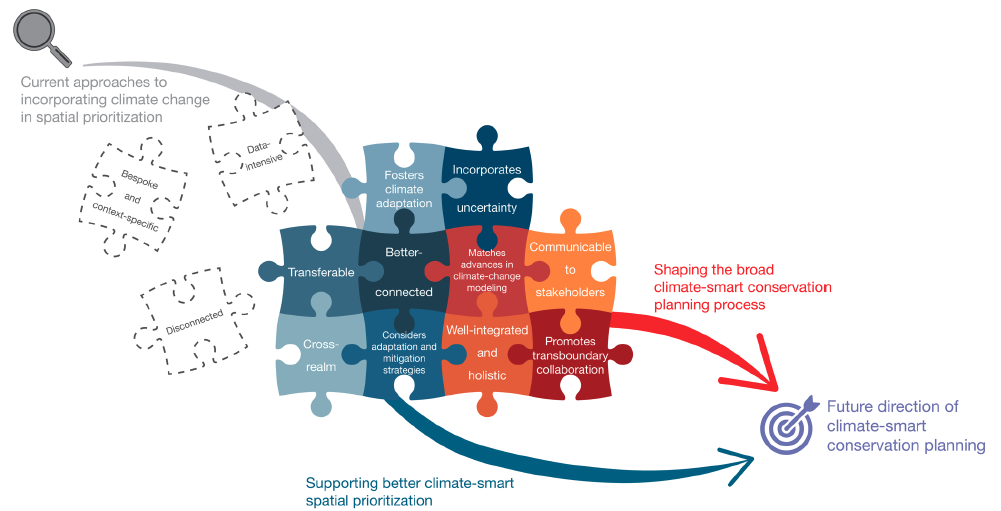

These climate-driven changes threaten to erode decades of conservation investment. Yet, climate change remains largely absent from most marine spatial planning (MSP) initiatives, where it is often treated as a secondary concern—when considered at all.This omission poses a serious risk: without integrating climate information into conservation decisions, we risk misallocating resources, misjudging future biodiversity patterns, and leaving marine ecosystems — and the communities that depend on them — increasingly vulnerable.

Our Solution: Climate-smart protected areas

We have developed multiple approaches for designing climate-smart protected areas. These preferentially place protected areas in climate refugia or climate adaptation hotspots (see Publications – Buenafe et al. (2025); Buenafe et al. (2023); Brito-Morales et al. (2022); Arafeh Dalmau et al. (2021)). Our methods are based on global Earth System Models and are thus ideal for data-poor regions, and in small regions we use data from high resolution climate models (10 km). These methods can be included in our shinyplanr real-time spatial planning app.